What Is Medicine?

1. The Science of Healing; the practice of the diagnosis, treatment and prevention of disease, and the promotion of health.

2. Medications, drugs, substances used to treat and cure diseases, and to promote health.

This series of articles focus on the science of healing, its history from prehistoric times until today, and the medications and healing methods used.

Some people might call medicine a regulated patient-focused health profession which is devoted to the health and well-being of patients.

Whichever way medicine is described, the thrust of the meaning is the same - diagnosis, treatment and prevention of disease, caring for patients and a dedication to their health and well-being.

According to Medilexicon's medical dictionary, Medicine is:

1. A drug.

2. The art of preventing or curing disease; the science concerned with disease in all its relations.

3. The study and treatment of general diseases or those affecting the internal parts of the body, especially those not usually requiring surgical intervention.

Modern medicine includes many fields of science and practice, including:

- Clinical practice - the physician assesses the patient personally; the aim being to diagnose, treat, and prevent disease using his/her training and clinical judgment.

- Healthcare science - a multidisciplinary field which deals with the application of science, technology, engineering (mathematics) for the delivery of care. A healthcare scientist is involved with the delivery of diagnosis, treatment, care and support of patients in systems of healthcare, as opposed to people in academic research. A healthcare scientist actively combines the organizational, psychosocial, biomedical, and societal aspects of health, disease and healthcare.

- Biomedical research - a broad area of science that seeks ways to prevent and treat diseases that make people and/or animals ill or causes death. It includes several areas of both physical and life sciences. Biomedical scientists use biotechnology techniques to study biological processes and diseases; their ultimate objective is to develop successful treatments and cures. Biomedical research requires careful experimentation, development and evaluations involving many scientists, including biologists, chemists, doctors, pharmacologist, and others. It is an evolutionary process.

- Medications - drugs or medicines and their administration. Medications are chemical substances meant for use in medical diagnosis, treatment, cure, or prevention of disease.

- Surgery - a branch of medicine that focuses on diagnosing and treating disease, deformity and injury by instrumental and manual means. This may involve a surgical procedure, such as one that involves removing or replacing diseased tissue or organs. Surgery usually takes place in a laboratory, operating room (theater), a dental clinic, or a veterinary clinic/practice.

- Medical devices - instruments, implants, in vitro reagents, apparatuses, or other similar articles which help in the diagnosis of diseases and other conditions. Medical devices are also used to cure disease, mitigate harm or symptoms, to treat illness or conditions, and to prevent diseases. They may also be used to affect the structure or function of parts of the body. Unlike medications, medical devices achieve their principal purpose (action) by mechanical, thermal, physical, physic-chemical, or chemical means. Medical devices range from simple medical thermometers to enormous, sophisticated and expensive image scanning machines.

- The History of Medicine - humans have been practicing medicine in one way or another for over a million years. In order to understand how modern medicine got to where it is now, it is important to read about the history of medicine. In this series of articles you can read about:

- Prehistoric Medicine

- Ancient Egyptian Medicine

- Ancient Greek Medicine

- Ancient Roman Medicine

- Medieval Islamic Medicine

- Medieval and Renaissance European Medicine

- Medicine from the 18th century until today

- Alternative medicine - includes any practice which claims to heal but does not fall within the realm of conventional/traditional medicine. In most cases, because it is based on cultural or historical traditions, instead of scientific evidence. Scientific refers to, for example, demonstrating the effectiveness or a therapy or drug in a double-blind, random, long-term, large clinical human study (clinical trial), in which the therapy or drug is compared to either a placebo or another therapy/drug. Examples of alternative medicine include homeopathy, acupuncture, ayurveda, naturopathic medicine, and traditional Chinese medicine.

- Psychotherapy, physical therapy (UK: physiotherapy), occupational therapy, nursing, midwifery, and several other fields

"The sum total of the knowledge, skills, and practices based on the theories, beliefs, and experiences indigenous to different cultures, whether explicable or not, used in the maintenance of health as well as in the prevention, diagnosis, improvement or treatment of physical and mental illness."

There are many branches in medicine, below is a list of some of them (there are many more):

- Anatomy - the study of the physical structure of the body

- Biochemistry - studies what chemical components are and what they do in the body

- Biomechanics - studies how biological systems in the body work, as well as their structure. This is done using mechanics.

- Biostatistics - applying statistics to biological fields. Biostatistics is crucial for successful medical research as well as many areas of medical practice.

- Biophysics - uses physics, mathematics, chemistry and biology to model and understand the workings of biological systems.

- Cytology - a branch of pathology, the medical and scientific microscopic study of cells

- Embryology - a branch of biology which studies the formation, early growth and development of organisms.

- Endocrinology - the study of hormones and their impact on the body

- Epidemiology - the study of causes, distribution and control of diseases in populations.

- Genetics - the study of genes.

- Histology - studies the form of structures under the microscope. Also known as microscopic anatomy.

- Microbiology - the study of organisms that are too small to see with the naked eye - microorganisms. Included in this field are bacteriology, virology, mycology (study of fungi), and parasitology.

- Neuroscience - the study of the nervous system and the brain. Included in this field are diseases of the nervous system, computational modeling, psychophysics, cognitive neuroscience, cellular neuroscience, and molecular neuroscience.

- Nutrition - studying how food and drink influence health and help treat, cure and prevent diseases and conditions which influence on disease risk.

- Pathology - the study of disease. A branch of medicine which looks at the essential nature of disease.

- Pharmacology - the study of pharmaceutical medications (drugs), where they come from, how they work, how the body responds to them, and what they consist of.

- Physiology - studying how living organisms exist, how they feed themselves, move and reproduce.

- Radiology - the use of ionizing and non-ionizing radiation to diagnose and treat disease.

- Toxicology - studying poisons, what they are, what effects they have on the body, and how to detect them.

What Is Prehistoric Medicine?

Prehistoric medicine refers to medicine before humans were are to read and write. It covers a vast period, which varies according to regions and cultures. Anthropologists, people who study the history of humanity, can only make calculated guesses at what prehistoric medicine was like by collecting and studying human remains and artifacts. They have sometimes extrapolated from observations of certain indigenous populations today and over the last hundred years whose lives have been isolated from other cultures.People in prehistoric times would have believed in a combination of natural and supernatural causes and treatments for conditions and diseases. The practice of comparing a placebo effect with a given therapy did not exist. There may have been some trial and error in coming to some effective treatments, but they would not have taken into account several variables scientists factor in today, such as coincidence, lifestyle, family history, and the placebo effect.

Nobody can be absolutely certain what prehistoric peoples knew about how the human body works. However, we can make some calculated guesses, based on some limited evidence. There is evidence from their burial practices that they knew something about bone structure. Bones have been found that were stripped of the flesh, bleached and piled according to what part of the body they came from.

There is also archeological evidence of cannibalism among some of the prehistoric communities - so, they must have known about our inner organs and where lean tissue or fat predominates in the human body. Most likely, they believed that their lives were determined by spirits. Aboriginals peoples around the world today often correlate illness with losing one's soul.

The aboriginals in Australia were described by colonists as being able to stitch up wounds, and encased broken bones in mud to set them right. Medical historians believe these skills probably existed during prehistory. However, most evidence found in prehistoric graves shows healthy but badly set bones, indicating that they did not know how to set broken bones.

There was no concept of public health in prehistoric times

Homo Habilis, who lived about 2.33 to

1.4 million years ago, probably the first

prehistoric humans to use tools. They were

hunter-gatherers and most likely suffered

many cuts and skin wounds

During pre-history, people were afflicted with ailments and diseases, just like we are today. However, because of very different lifestyles and lifespans, they did not suffer from the same diseases so commonly.

Below are some diseases and conditions which were probably very common in prehistoric times:

- Osteoarthritis - many people had to lift and carry large and heavy object frequently. According to archeological remains, osteoarthritis was common.

- Micro-fractures of the spine and spondylolysis - large rocks were commonly dragged over long distances.

- Hyper-extension and torque of the lower back - caused by the transport and raising of massive rocks and stones, such as Latte Stones.

- Infections and complications - people were hunter gatherers and were much more likely to suffer cuts, bruises and bone fractures. There were no modern antibiotics, vaccines, antiseptics, and most likely no knowledge of bacteria, viruses, funguses and other harmful pathogens and the impact of good hygiene practices in preventing infection complications. Infections were much more likely to become serious and life-threatening, while contagious diseases used to spread rapidly and turn into epidemics easily.

- Rickets - anthropologists have evidence that rickets was widespread throughout most prehistoric communities, probably due to low vitamin D levels.

- Life expectancy - this ranged from about 25 to 40 years, depending on regions and per-historic periods. People would have been much more susceptible to the ravages of nature, such as a decade-long cold period (or longer), droughts, floods, and diseases which killed off large numbers of their food sources. Men lived longer than women, probably because males were the hunters; they would have had access to their kills before the women, and possibly suffered less from malnutrition.

What medications did prehistoric people use?

Prehistoric people did use medicinal herbs, say anthropologists. Although we have some limited evidence of herbs and substances derived from natural sources used as medicines, it is very hard to be sure what the full range might have been, because plants rot rapidly.Anthropologists have had to go with what little evidence they may have gathered from the past, plus observing indigenous peoples today and over the last couple of centuries. We can be sure that any medicinal herb or plant would have been a local one - there was hardly any trade going on, and definitely no long-distant commerce. Nomadic tribes may have had access to a wider range of materials.

There is some evidence from present-day archeological sites in Iraq that mallow and yarrow were used about 60,000 years ago:

- Yarrow ( Achillea millefolium) is said to be an astringent (causes contraction of tissues, helps reduce bleeding), stimulant, diaphoretic (promotes sweating), and a mild aromatic. It was probably used for wounds, cuts and abrasions.

- Mallow - may have been prepared as a herbal infusion for its colon cleansing properties.

- Rosemary - there is evidence in several parts of the world that it was used as a medicinal herb. It is claimed to have so many different medicinal qualities, depending on which part of the world one is in, that it is difficult to be sure what it was used for.

- Birch Polypore (Piptoporus betulinus), a plant common in the European Alps, may have been used as a laxative. Archeologists found traces of this plant in a mummified man. Botanists say the plant can induce diarrhea when ingested.

Geophagy and Trepanning were probably practiced by prehistoric peoples

Geophagy refers to eating soil-like or earthy substances, such as chalk and clay. Animals and humans have done this for hundreds of thousands of years. In Western and industrialized societies geophagy is related to pica, an eating disorder.Prehistoric humans probably had their first medicinal experiences through eating earths and clays. They may have copied animals, observing how some clays, when ingested, may have had healing qualities. Some clays are useful for treating wounds. Several aboriginal peoples worldwide use clay externally and internally for the treatment of cuts and wounds.

Trepanning - drilling a hole into the human skull for the treatment of health problems. There is evidence that since Neolithic times, humans have been boring holes into people's heads in an attempt to cure diseases or free the victim of demons and evil spirits.

A Human skull with trepanations at Monte Albán - Museo del Sitio (Del Sitio Museum)

According to cave paintings, anthropologists believe that they were used in an attempt to cure people of mental disorders, migraines and epileptic seizures. The extracted bone may have been kept by the patient as a good-luck charm.

There is also evidence that trepanning was used in prehistorical times to treat fractured skulls.

The Medicine man or Shaman

Medicine men, also known as witch-doctors or shamans existed in some prehistoric communities. They were in charge of their tribe's health and gathered plant based medications, mainly herbs and roots, carried out rudimentary surgical procedures, as well as casting spells and charms. Tribespeople would also seek them out for medical advice.

What Is Ancient Egyptian Medicine?

Ancient Egypt (3300BC to 525BC) is where we first see the dawn of what, today, we call "medical care". The Egyptian civilization was the first great civilization on this planet. Egyptians thought gods, demons and spirits played a key role in causing diseases. Many doctors at the time believed that spirits blocked channels in the body, and affected the way the body functioned.Their research involved trying to find ways to unblock the "Channels". Gradually, through a process of trial and error and some basic science, the profession of a "doctor of medicine" emerged. Ancient Egyptian doctors used a combination of natural remedies, combined with prayer.

Unlike prehistoric peoples, ancient Egyptians were able to document their research and knowledge, they were could read and write; they also had a system of mathematics which helped scientists make calculations. Documented ancient Egyptian medical literature is among the oldest in existence today.

The ancient Egyptians had an agricultural economy, organized and structured government, social conventions and properly enforced laws. Their society was stable; many people lived their whole lives in the same place, unlike most of their prehistoric predecessors. This stability allowed medical research to develop. In this society, individuals were relatively wealthy, compared to their ancestors, and could afford health care.

They had temples, priests and rituals in which deceased people were mummified. In order to mummify you have to learn something about how the human body works. In one mummification process, a long hooked implement was inserted through the nostril, breaking the thin bone of the brain case, allowing the brain to be removed. A significant number of priests became medical doctors.

Ancient Egyptian doctors knew that the body had a pulse, and that it was associated with the function of the heart. They had a very basic knowledge of a cardiac system, but overlooked the phenomenon of blood circulating around the body - either because they missed it, or thought it did not matter, they were unable to distinguish blood vessels, nerves, or tendons.

The ancient Egyptians were traders, and travelled long distances, coming back with herbs and spices from faraway lands. Their relatively high standard of living gave them free time, which they could use for observing things and thinking about them. Medical research involves patience and observation.

The Channel Theory and how the Gods impacted on human health

The Channel Theory - this came by observing farmers who dug out irrigations channels for their crops. They believed that as in irrigation, channels provided the body with routes for good health. If the channels became blocked, they would use laxatives to unblock them.They thought the heart was the center of 46 channels - types of tubes. To a certain extent, they were right, our veins, arteries, and even our intestines are types of tubes. However, they never came to realize that these channels had different functions.

The Gods were the creators and controllers of life, the Egyptians thought. They believed conception was done by the god Thoth, while Bes, another god, decided whether childbirth went smoothly. Blockages in the human "channels" were thought to be the result of the evil doings of Wehedu, an evil spirit.

The channel theory allowed medicine to move from entirely spiritual cures for diseases and disorders, towards practical ones. Many medical historians say this change was a major turning point, a breakthrough in the history of medicine.

Doctors gave "good" and "bizarre" medical advice

Some recommendations made by physicians were fairly sound - they advised people to wash and shave their bodies as measures to prevent infections. They told people to eat carefully, and to avoid unclean animals and raw fish.Some of their practices were bizarre, however, and most likely did more harm than good. Several medical prescriptions contained animal dung, which might have useful molds and fermentation substances, but were also infested with bacteria and must have caused many serious infections.

Ancient Egyptian medicine was highly advanced for its time

Egyptian doctors were sought after by kings and queens from faraway lands because they were considered as the best in the world.Archeologists have found Papyri (thick paper-like material produced from the pith of the papyrus plant) where Egyptians had documented a vast amount of medical knowledge. They found that they had fairly good knowledge about bone structure, and were aware of some of the functions of the brain and liver.

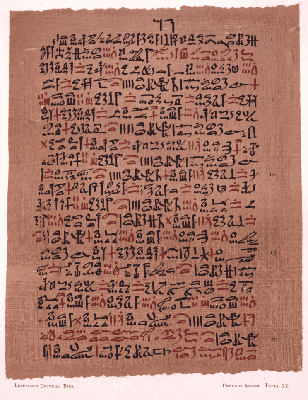

The Ebers Papyrus (Papyrus Ebers)

These are medical documents which are thought to have been written around 1500 BC, and most likely include retranscribed materials dating back to 3400 BC. It is a 20-meter long scroll, which covers the equivalent of approximately 100 pages. The Ebers Papyrus, along with the Edwin Smith Papyrus, are the oldest preserved medical documents in existence.Georg Moritz Ebers (1837-1898), a German novelist and Egyptologist, discovered this medical papyrus at Thebes (Luxor) in 1873-74. It is now in the Library of the University of Leipzig, Germany.

The Ebers Papyrus was has over 700 remedies and magical formulae, as well as scores of incantations aimed at repelling demons which cause disease. However, it also has evidence of sound scientific procedures.

The authors wrote that the center of the body's blood supply is the heart, and that every corner of the body is attached to vessels. The functions of some organs appear to have been overlooked, while the heart was the meeting point for vessels which carried tears, urine, semen and blood.

The Book of Hearts, a section of the Ebers Papyrus, described in great detail the characteristics, causes, and treatment for such mental disorders as dementia and depression. It appears they viewed mental diseases as a combination of blocked channels and the influence of evil spirits and angry Gods.

There is even a section on family planning, contraception, how to tell if you are pregnant, and some other gynecological issues. They wrote about skin problems, dental problems, diseases related to the eyes, intestinal disease, parasites, and how to surgically treat an abscess or a tumor. The ancient Egyptians clearly knew how to set broken bones and treat burns.

Below are some quotes from the Ebers Papyrus (adapted into familiar modern day phrases:

- From the heart there are vessels to all four limbs, to every part of the body. When a doctor, Sekmet priest or exorcist place their hands on any part of a person's body, they are examining the heart, because all vessels come from the heart. The heart is the source, and speaks out to every part of the body.

- When we breathe in through our noses, the air enters our hearts and lungs, and then the entire belly.

- The nostrils have four vessels. Two of them provide mucus while the other two provide blood.

- The human body has four vessels which lead to two ears. Into the right ear enters the "breath of life", while into the left ear the "breath of death" enters.

- Baldness is caused by four vessels to the head.

- All eye diseases originate from four vessels in the forehead which provide the eyes with blood.

- Two vessels enter a man's testicles and provide them with semen.

- The buttocks have two vessels which supply them with vital nutrients.

- Six vessels reach the soles of our feet.

- Six vessels lead to our fingers, through our arms.

- The bladder is connected to two vessels. They supply it with urine.

- The liver is supplied with liquid and air via four vessels. When they overfill the liver with blood, they cause many diseases.

- The lungs and spleen are connected to four vessels, which like the liver, are supplied with liquid and air.

- The liquid and air that come out of the anus come from four vessels. The anus is also exposed to all the vessels that exist in the arms and legs when they are overflowing with waste.

Egyptian doctors were adept at some basic surgical procedures

Egyptian physicians were trained and good at practical first aid. They could successfully fix broken bones and dislocated joints.Basic surgery, meaning procedures close to the surface of the skin (or on the skin) was a common and well learnt skill. They knew how to stitch wounds effectively. They did not, however, perform surgery deep inside the body. They had no effective anesthetics, only antiseptics. Performing surgery deep inside a human body would have been impossible.

They had excellent bandages, and would bind certain plant products, such as willow leaves, into the bandages for the treatment of inflammation.

Circumcision of baby boys was common practice. It is hard to tell whether female circumcision existed; there is one mention, but several experts believe the text has not been translated properly.

Egyptian doctors said there were three types of injuries:

- Treatable injuries - these were dealt with immediately.

- Contestable injuries - these were deemed not to be life-threatening, i.e. the doctor believed the patient could survive without his intervention. Patients would be put under observation. If they survived, the doctor would decide in his own time whether to intervene.

- Untreatable ailments - the meaning is clear; the doctor would not intervene.

Ancient Egyptian inscriptions illustrating bone

saws, scales, lances, dental tools, suction

cups, knives and scalpels

Prosthetics did exist, but archeologists say they were probably not that practical and were used either to make deceased people look more presentable during funerals, or were simply for decorative purposes.

Ancient Egyptian public health

The aim of public health is to protect the community from the spread of disease, and too keep everybody as healthy as possible. The provision of water so that people can wash themselves, their animals and their homes is a vital part of preventing the spread of disease. Cleanliness was an important part of Egyptian life; however, it was promoted for social and religious reasons, and not health ones.Their homes had rudimentary baths and toilets. Personal cleanliness and appearance were an important part of life; many even wore make-up around their eyes to protect from disease. Most people used mosquito nets during the hot months - we cannot know whether this was to protect against malaria and other diseases, or simply because they did not want to be bitten.

Priests washed themselves and their clothing and eating utensils regularly. But they did it for religious reasons. Although hygiene practices did help protect their health, this was not their reason. Cleanliness was an appeal to their gods.

There was no public health infrastructure as we know of today, with sewage systems, proper medical care and public hygiene.

Magic and religion to treat illnesses

Everyday life in Egypt involved beliefs and fear of magic, gods, demons, evils spirits, etc. Luck and disaster were caused by angry celestial beings or evil forces. They believed that if illnesses and physical and mental disorders were partly caused by supernatural forces, then magic and religion were required to deal with them and treat people.Anthropologists, archeologists, and medical historians say there did not appear to be a clear difference between a priest and a doctor in those days. Many healers were priests of Sekhmet, and used science as well as magic and incantations when treating people. (Sekhmet was an Egyptian warrior goddess).

The religious and/or magic rituals and procedures probably had a powerful placebo effect, which were likely seen as proof of their effectiveness.

Some treatments used products or herbs or plants that looked similar to the illness they were treating, this is known as simila similibus (similar with similar). This practice has existed all over the world, even in modern alternative medicine (homeopathy, treating like with like). In Egyptian times ostrich eggs were used to treat a fractured skull.

The medical profession had a structure and a hierarchy

The earliest ever record of a physician was Hesy-Ra, 2700 BC, who was "Chief of Dentists and Doctors" to King Dioser.The first female doctor was probably Peseshet 2400 BC, who was known as the supervisor of all female doctors.

The top doctors worked in the royal court. Below them there were inspectors who would supervise the proper actions of doctors. There were specialists, such as dentists, proctologists, gastroenterologists, and ophthalmologists. A proctologist was called "nery phuyt" which means "shepherd of the anus".

What Is Ancient Greek Medicine?

As the Egyptian civilization faded, the Greek one emerged around 700 BC. The Greek civilization prevailed until "the end of antiquity" around 600 AD. The Greeks were great philosophers and their physicians lent more towards rational thinking when dealing with medicine, compared to the Egyptians. Ancient Greek medicine is probably the basis of modern scientific medicine.The first schools to develop in Greece were in Sicilly and Calabria, in what today is Italy. The most famous and influential being the Pythagorean school. Pythagoras, the great mathematician, brought his theory of numbers into the natural sciences - at that time medicine was not yet a definable subject.

Followers of Pythagoras, Pythagoreans, believed that numbers had precise meanings, especially the numbers 4 and 7. They mentioned that the Bible refers to infinity as 70x7, and that 7x4 is the duration of the lunar month as well as the menstrual cycle (28 days), 7x40 is 280 which is how long a pregnancy is when it reaches full term. They also believed that a baby would enjoy better health if he/she was born on the seventh month rather than the 8th.

The 40-day quarantine period to avoid disease contagion comes from the idea that the number forty is sacred.

According to ancient records, another early Greek medical school was set up in Cnidus in 700 BC. Alcmaen worked at this school, where the practice of observing patients began.

Alcmaeon (circa 500BC) of Croton is considered as one of the most eminent medical theorists and philosophers in ancient history. Some believe he was a student of Pythagoras. He wrote widely on medicine; however, some historians say he was probably a philosopher of science, and perhaps not a physician. As far as we know, he was the first person to wonder about the possible internal causes of illness. He put forward the idea that illness may be caused by environmental problems, nutrition and lifestyle.

Greek civilization was very different form the Egyptian one. The Egyptian empire was ruled by a monarch, while the Greek system involved several city-states which were ruled by local governments. Athens was democratic, its people voted rulers in, while Macedon was a dictatorship and Sparta was under military rule. Ancient Greece had a variety of systems.

Apart from being great traders, the Greeks were relatively wealthy; they promoted and enjoyed culture and adored poetry, public debates, politics, architecture, sculpture, comedy and drama. Their writing was phonetic, meaning it could be read out loud; a much more flexible form of written communication compared to the hieroglyphs the Egyptians used.

Their thirst for logic and logically-based discussions meant that mathematics and science could really develop.Aristotle, a mathematician, thrived in the Greek system. Socrates, a teacher, promoted the concept of asking questions into teaching methodologies.

From 600 BC onwards, the Greeks became more and more inquisitive about things around them - their discussions on why things exist, why they happen were approached rationally.

In 600 BC Anaximander put forward the idea that all matter was made up of earth, water, air and fire - which he called elements. It was not long before Greek physicians wondered whether all illnesses and disorders might not have a natural cause, and if so, would they not better respond to natural cures, rather than incantations and attempts at repelling evil spirits, like the Egyptians did.

Around 300 BC Alexander the Great had turned Greece into a massive empire, which spread all over the Middle East. The city of Alexandria was built in Egypt, and became a vast center for education and learning.

Although they still believed in and had their gods, science gradually took over when trying to explain the reason and solution for illness and other things in general.

The ancient Greeks believed medicine revolved around the theory of humors.

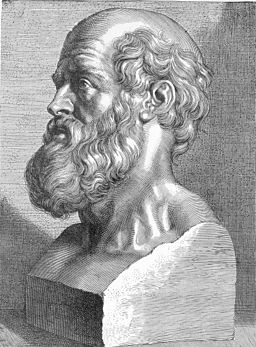

The most famous, and probably the most important medical figure in Ancient Greece was Hippocrates, who is known today as "The Father of Medicine".

Hippokrates of Kos, The Father of Western Medicine

Hippocrates of Kos (or Cos) (460 BC - 370 BC) is considered as one of the giants in the history of medicine in recognition for his contributions to the medical field as founder of the Hippocratic School of Medicine. What was taught at his school revolutionized medicine - it was established as a discipline in its own right. Up until then, medicine was linked to philosophy and the practice of rituals, casting off evil spirits and incantations (Theurgy). It was Hippocrates' and his school's teachings which established medicine as a profession.The Hippocratic Corpus, written by Hippocrates and colleagues at his school, consisted of about 60 early Ancient Greek medical works. Medical historians say it is impossible to tell what was written by him or other people.

Hippocrates is credited with creating the Hippocratic Oath, a vow taken by medical students when they become qualified doctors. The oath is also taken today by other healthcare professionals. They swear to practice medicine ethically and honestly. Some classical scholars, such as Ludwig Edelstein, believe that the oath was created by Pythagoreans. Nobody is completely sure who wrote it.

It is believed that Hippocrates advanced the systematic study of clinical medicine, i.e. the study of disease by direct examination of the living patient.

Medical historians say that Hippocrates and those practicing or having studied at his school were bound by the Hippocratic Oath and its strict ethical code. Students paid a fee to enter the school and were taken under their teacher's wing almost as if they were of the same family. Medical training would have included oral teaching and practical work as a teacher's assistant - the Oath states that a student must interact with patients.

Hippocrates and those from his school where the first people to describe and properly document several diseases and disorders. Hippocrates is thought to be the first to make a detailed description of clubbing of the fingers, a hallmark sign of chronic suppurative lung disease, cyanotic heart disease, and lung cancer. Some doctors today when making a diagnosis, will write "Hippocratic fingers" when referring to clubbed fingers.

The Hippocratic Face - this is a description of a face not long before death. It is a prognostic description, made by Hippocrates:

"(If the patient's facial) appearance may be described thus: the nose sharp, the eyes sunken, the temples fallen in, the ears cold and drawn in and their lobes distorted, the skin of the face hard, stretched and dry, and the colour of the face pale or dusky.... and if there is no improvement within [a prescribed period of time], it must be realized that this sign portends death."

Hippocrates and his school were the first to use the following medical terms for illnesses and patients' conditions:

- Acute

- Chronic

- Endemic

- Epidemic

- Convalescence

- Crisis

- Exacerbation

- Paroxysm

- Peak

- Relapse

- Resolution

How Aristotle and Plato influenced medical practice and research

Two famous Greek philosophers, Aristotle (384 BC - 322 BC) and Plato (424/423 BC - 348/347 BC) came to the conclusion that the human body had no use in the afterlife. This new way of thinking spread and influenced Greek doctors, who at Alexandria, Egypt, starting dissecting dead bodies and studying them. Sometimes even bodies of live criminals were cut open. It was through this kind of research that the surgeon Herophilus (335-280 BC) came to the conclusion that it was not the heart that controlled the movement of limbs, but the brain.Erasistratus (304 BC - 250 BC) found out that blood moves through the veins - however, he overlooked the fact that it circulates).Aristotle's and Plato's philosophies, writings and speeches allowed the Greeks to start finding out about the inside of the human body in a systematic way.

Thucydides (circa 460 BC - circa 395 BC), a Greek historian, often called the "Father of Scientific History", came to the conclusion that prayers were totally ineffective against illnesses and plagues. He added that epilepsy had a scientific explanation and had nothing to do with angry gods or evil spirits.

Thycydides wrote, in his work 'History of the Peloponnesian War':

"I shall describe what the plague was like ... At the beginning the doctors were unable to treat the disease because of their ignorance of the right methods. Equally useless were prayers in the temples, consulting the oracles and suchlike."

The great minds of the time pushed science forward, so that medical professionals, scientists and researchers could seek out entirely natural theories for the cause of diseases.

The Four Humors in the Human Body

At that time, everybody thought that natural matter was made of four basic elements - earth, water, air and fire. It was not long that this theory gave them the idea that the human body consisted of the four humors, and that keeping those humors in balance was essential for good health. This theory survived for nearly 2,000 years (up to 1700 AD).The four humors in the human body were:

- Blood

- Phlegm

- Yellow bile

- Black bile

Did the Greeks perform surgery?

We know the Greeks dissected dead bodies, and even live ones sometimes to find out what was going on inside. Medical historians doubt whether they performed internal surgical operations.There were always some Greek states at war, which gave doctors vast experience in practical first aid, and they became skilled experts.

Greek doctors were good at setting broken bones and fixing dislocated ones. They could even cure a slipped disc.

As in Ancient Egypt, the Greeks had no anesthetics, and only some herbal antiseptic mixes. Without anesthetics it is virtually impossible to perform surgery deep inside the human body.

How did Greek doctors diagnose and treat patients?

The methods for reaching diagnoses by Greek doctors were not that different from what happens today. Many of their natural remedies are similar to a number of effective home remedies we currently use. Their theory of the four humors though, was mainly an obstacle to medical practice. About two thousand years later, that theory was found to be false.Greek doctors would carry out a clinical observation; they performed a thorough physical examination of their patient. They would refer to their Hippocratic books for guidance on how to carry out the examinations and which diseases they should consider or try to rule out.

Over time, magic and appealing to gods gave way to seeking out natural causes for illnesses. This led to researching for natural cures. Greek doctors became expert herbalists and prescribers of natural remedies. They became convinced that the best healer is nature.

Hippocratic books mentioned:

- For chest diseases - barley soup, plus vinegar and honey, which would bring up phlegm.

- For pain in the side - dip a large soft sponge in water and apply gently. If the pain has reached the collar bone, then bleeding near the elbow is recommended until the blood flows bright red.

- For pneumonia - give the patient a bath, it relieves pain and helps him bring up phlegm. The patient must remain completely still in the bath.

- kept patients warm when they had a cold

- kept feverish and sweaty patients dry and cool

- bled patients to restore the blood balance

- purged patients to restore the bile balance. This would have been done by giving them laxatives, making them vomit, or giving them diuretics

Despite their apparent period of enlightenment, many doctors would still appeal to their Gods if treatments were not effective. Asklepios was the Greek god of healing, and there was a temple in Epidaurus, called Asklepion.

Some doctors would treat their patients and then take them to the abaton to spend the night asleep; the abaton was a holy place in a temple. They believed that Hygeia and Panacea, daughters of Asklepios would arrive with two holy snakes which would cure the patients. From "Hygeia" we have the word hygiene. The snake today is the symbol of pharmacists.

Did Ancient Greece have a public health system?

Authorities in Greece were not yet aware of the need for public health; the Greek city states did not strive to ensure their people had a good supply of water so they could wash themselves and keep their homes clean. There were no public sewage systems either.However, the people were great believers in staying healthy. Well off and educated Greeks worked at remaining at a constant temperature, cleaning their teeth, washing regularly, keeping fit, and eating healthily. Their aim was to keep the four humors in balance throughout the year.

Greek doctors were strong believers in doing things in moderations.

Out of every three children born, only two would ever reach the age of two years. The life-expectancy of a healthy Greek adult was about fifty years.

According to Hippocrates, poor people would be too focused on making ends meet to be too concerned about their overall health.

Even though religion was slowly making way to logical reasoning, people still called on their gods to heal them at the Asklepion. Eventually, these temples became health spas, gymnasiums, public baths, and sports stadiums.

What Is Ancient Roman Medicine?

Ancient Rome was a flourishing civilization that started around 800 BC and existed for approximately 1200 years. It started off in Rome, and grew into one of the largest and most powerful empires in ancient history. It was ruled initially by monarchs, then became an aristocratic republic, and shifted towards being a progressively more repressive empire. The empire spread to Southern, Western and parts of Eastern Europe, Asia Minor and North Africa. In many ways, the Roman and Greek empires shared a number values and systems.As far as health was concerned, the Romans were more interested in prevention than cure. Public health facilities were encouraged throughout the empire. Roman medicine grew out of what military doctors learnt and demanded.

Initially, the Romans resisted the practices and theories that came from Greece. Roman medicine did not go backwards after Greece, it took a slightly different direction. Eventually, Roman scientists and doctors, many of them from Greece, continued researching Greek theories of diseases and physical and mental disorders.

The Romans were great warriors; the empire poured considerable resources into the basis of its power - the armies. It was by observing their soldiers' health that Roman leaders began to realize the importance of public health.

Greece's influence, nevertheless, on Roman medicine was huge. The first doctors in Rome came from Greece; they were prisoners of war. Later on Greek doctors would emigrate to Rome because they would earn more money there than back home.

When the Romans conquered Alexandria, they found various libraries and universities which the Greeks had set up. There was a wealth of documented knowledge of medicine in Alexandria, as well as several learning centers and places for research. The Romans allowed them to carry on their research. However, unlike the Greeks, the Romans did not like the idea of dissecting dead people.

The Romans eventually adopted the Greek theory about the four humors. The spiritual beliefs that surrounded medicine in Greece was also common in Roman medicine.

Roman civilization developed into a massive empire, unlike the Greek civilization which consisted of many small city-states. The Roman empire was centralized; the emperor in Rome was all-powerful and wielded his power, will and laws throughout the empire.

Roman wealth went more into practical projects and less into culture and philosophy. The Romans built aqueducts to pipe water to cites, sewers in their capital city, and public baths everywhere. They were proud of their projects, which they described as "useful", and not "useless Greek buildings" or "idle Egyptian pyramids".

The sewage system in Rome was so advanced, that nothing like it was built again until the late 17th century AD. Despite their impressive projects which helped improve public health, they were not yet aware of the association of germs with diseases.

The Romans had tools, painkillers and hospitals

Roman surgeons, most of whom got their practical experience on the battlefield, carried a tool kit which contained arrow extractors, catheters, scalpels and forceps. They used to sterilize their equipment in boiling water before usage.Various Roman surgical tools found at Pompeii by archeologist Giorgio Sommer (1834-1914)

Surgical procedures were performed using opium and scopolamine as painkillers, and acid vinegar (acetum) to clean up wounds. They did not have what we would consider as effective anesthetics for complicated surgical procedures; it is doubtful they carried out surgical operations deep inside the body.

The Romans also had midwifery instruments, many of which would seem rather barbaric today. Cesarean sections were performed, but the mother would not survive.

Unlike the Greeks who would place their patients in temples in the hope that the gods might help cure them, the Romans had purpose-built hospitals where patients could rest and have a much better chance of recovering. In hospital settings, doctors were able to observe sick patients, instead of depending on supernatural forces to perform miracles.

By not allowing doctors to dissect corpses, Roman doctors were rather limited in human anatomy research. Even though some of their progress was undermined by initially rejecting Greek ideas about medicine, they made great progress in trying to understand what causes diseases, and then finding ways of preventing them.

How did Roman doctors learn about the human body?

Gladiators were often wounded, sometimes badly, and doctors had to treat them, and learnt about the human body. Galen (AD 129 - circa 200/216) , a prominent Greek physician, had to make do with dissecting animals to further his research. Galen believed that monkeys that walked like humans, on two legs, would most likely provide scientists with knowledge that could be applied to humans.Galen, who moved from Greece to Rome in 162AD, became an expert on human anatomy. He was a popular lecturer and soon became a well-known reputable, sought-after doctor. Consul Flavius Boethius, one of his patients, introduced him to the imperial court; he soon became Emperor Marcus Aurelius' personal physician.

Galen did dissect some corpses - once he dissected a hanged criminal, as well as some bodies that has become unearthed in a cemetery during a flood. Even so, he made several mistakes when analyzing how the human body works.

Galen wrote several medical books, in which he displayed excellent knowledge of bone structure. He realized that the brain tells muscles what to do when he cut the spinal cord of a pig and observed it.

Medical theories were sometimes very close to what we know today. Marcus Terentius Varro (116 BC - 27 BC) believed disease was caused by miniature creatures too small for the naked eye to see (bacteria and viruses are too small to see). Others were still looking up at the sky - Crinas of Massilia was sure that our illnesses were caused by the stars. Lucius Junius Moderatus Columella (AD 4 - circa AD 70), an agricultural writer, thought diseases came from swamp vapors. Many of these beliefs prevailed until a couple of hundred years ago.

How did Roman doctors diagnose and treat patients?

Roman physicians were strongly influenced by what the Greeks used to do, and would carry out a thorough physical exam of the patient. Many of their treatments were also influenced by Greek practices. Roman diagnosis and treatment of patients consisted of a combination of Greek medicine and some local practices.Some Roman doctors were impressive in their claims. Galen said that by following Greek practice he never misdiagnosed or made a wrong prognosis. Progress in diagnosis, treatment and prognosis in Ancient Rome was slow and patchy; doctors tended to develop their own theories and diverged in several different directions.

They did have a wide range of herbal medicines and other remedies:

- Fennel - was widely used for people with nervous disorders. Romans believed fennel calmed the nerves.

- Unwashed wool - was used for sores

- Elecampane (horse heal) - was given to patients with digestive problems.

- Egg yolk - was given to patients with dysentery

- Sage - said to have had more religious value, and used by those who still believed that the gods could heal them.

- Garlic - doctors said garlic was good for the heart

- Boiled liver - was administered to patients with sore eyes

- Fenugreek - often administered to patients with lung diseases, especially pneumonia

- Silphium - was used as a form of contraceptive, as well as for fever, cough, indigestion, sore throat, aches and pains, warts. Nobody is sure what Silphium was; historians believe it is an extinct plant of the genusFerula, possibly a variety of giant fennel.

- Willow - used as an antiseptic

Many Roman doctors came from Greece and strongly believed in achieving the right balance of the four humors and restoring the natural heat of patients.

Galen said that opposites would often cure patients. For a cold he would give the patient hot pepper. If a patient had a fever, he advised doctors to use cucumber.

The Romans believed in public health

Public health is all about maintaining the whole community in good health, and today involves preventing the spread of disease, vaccination programs, promoting healthy lifestyles and good eating habits, building hospitals, providing clean water for people to drink and wash themselves, etc. The Romans, unlike the Greeks and Egyptians, were strong believers in public health. They knew that hygiene was vital to prevent the spread of diseases.They promoted facilities for personal hygiene in a big way by building public baths, toilets and sewage systems. Although their focus was on maintaining a motivated and healthy army, their citizens also benefited.

Public baths - there were nine public baths in Rome alone. Each one had pools of varying temperatures. Some of them had gyms and massage rooms. Government inspectors enforced high hygiene standards vigorously.

Hospitals - hospitals started in Ancient Rome. The first ones were built to treat soldiers and veterans.

The Romans were superb engineers and built several aqueducts to supply people with water.

They were careful to place army barracks well away from swamps. If marshes got in the way, they would drain them. The Romans were aware of the link between swamps and mosquitoes and the diseases they could transmit to humans.

What Is Medieval Islamic Medicine?

Medicine was an important part of medieval Islamic life; both rich and poor people were interested in health and diseases. Islamic doctors and a number of scholars wrote profusely on health and developed extensive and complex medical literature on medications, clinical practice, diseases, cures, treatments and diagnoses. Unlike medical literature today, which is specialized, in the medieval Islamic world it was integrated with natural science, astrology, alchemy, religion, philosophy and mathematics.Islamic medicine built on the legacies left behind by Greek and Roman physicians and scholars. Islamic physicians and scholars were strongly influenced by Galen and Hippocrates, who were viewed as the two fathers of medicine, closely followed by the Greek scholars of Alexandria, Egypt. Most medical literature from both the Greek and Roman civilizations was translated into Arabic, and was later adapted to include their own findings and conclusions.

Islamic scholars were experts in gathering data and placing them in order so that readers could find them easier to understand and search backwards and forwards through various texts. They turned many of the Greek and Roman writings into summaries and encyclopedias.

Put simply, Islamic medicine built on Greek medical tradition and then formed its own. In fact, it was through reading Arabic versions that Western doctors learned of Greek medicine, including the works of Hippocrates and Galen.

The vessels anatomy chart from the collection

of Sami Ibrahim Haddad. Islamic publications

were vastly superior in paper and printing

quality than anything the Greeks or Romans

had

From 661 to 750 AD, an early Islamic period called Umayyad, people generally believed that Allah (God) would provide treatment for every illness. By 900 AD Islam started to develop and practice a medical system slanting towards science.

As people became more interested in health and health sciences from a scientific point of view, Islamic doctors strived to find healing procedures, with Allah's permission, that looked at the natural causes and potential treatments and cures.

The Medieval Islamic world produced some of the greatest medical thinkers in history, they also made advances in surgery, built hospitals, and welcomed women into the medical profession.

Al-Razi and Ibn Sina, two important medical thinkers

Muhammad ibn Zakariyā RāzīMuhammad ibn Zakariyā Rāzī (Al-Razi) (865-925), was a Persian physician, chemist, alchemist, philosopher and scholar. He was the first to distinguish measles from smallpox. He also discovered the chemical kerosene, as well as several other compounds. He became chief physician of Baghdad and Rey hospitals.

The eminent British historian, Edward Granville Browne (1862 - 1926), said that Al-Razi was "probably the greatest and most original of all the physicians and one of the most prolific as an author". Razi wrote over 200 scientific books and articles.

Al-Razi, known as the "father of pediatrics", was a great believer in experimental medicine. He wrote a book called The Diseases of Children, which is probably the first ever to place pediatrics as a separate field of medicine. He also pioneered ophthalmology. He travelled all over Persia teaching medicine. He is said to have been compassionate about treating both rich and poor patients equally.

Al-Razi was the first doctor to write about immunology and allergy. He is thought to have discovered allergic asthma. He was the first person to explain that fever is part of the body's defense mechanism for fighting disease and infection.

He was also a pharmacist and wrote extensively on the subject, introducing the use of mercurial ointments. Many devices are attributed to him, including spatulas, flasks, mortars, and phials. Regarding medical ethics, Al-Razi wrote:

"The doctor's aim is to do good, even to our enemies, so much more to our friends, and my profession forbids us to do harm to our kindred, as it is instituted for the benefit and welfare of the human race, and God imposed on physicians the oath not to compose mortiferous remedies."

He also believed that demons could posses the body and cause mental illness; a common belief at the time.

Abū ʿAlī al-Ḥusayn ibn ʿAbd Allāh ibn Sīnā

Abū ʿAlī al-Ḥusayn ibn ʿAbd Allāh ibn Sīnā (c. 980 -1037), often referred to as Ibn Sina or Avicenna (Latinized name) was a Persian polymath (one with numerous skills and professions) who was a prolific writer. Of 450 books and articles written by him, 240 still exist today, of which 40 focus on medicine.

Ibn Sina wrote The Book of Healing, an enormous scientific encyclopedia, as well as The Canon of Medicine, which became essential reading at several medical schools around the world, including the universities of Leuven (Belgium) and Montpellier (France) up to the middle of the sixteenth century. His book was based on the principles of Hippocrates and Galen.

The Canon of Medicine (The Law of Medicine) consists of a 5-volume encyclopedia. It was originally written in Arabic and later translated into several languages, including English, French and German. It is considered one of the most famous and influential books in the history of medicine.

The Canon of Medicine set the standards for medicine in both the Islamic world and Europe. The book is also the basis for a form of traditional medicine in India, known as Unani medicine. The UCLA and Yale Universities in the USA still teach some of the principles described in this work as part of the history of medicine curriculum.

George Sarton (1884-1956), a Belgian chemist and eminent historian, considered as the founder of the discipline of the history of science, wrote in one of his books the Introduction to the History of Science:

"One of the most famous exponents of Muslim universalism and an eminent figure in Islamic learning was Ibn Sina, known in the West as Avicenna (981-1037). For a thousand years he has retained his original renown as one of the greatest thinkers and medical scholars in history. His most important medical works are the Qanun (Canon) and a treatise on Cardiac drugs. The 'Qanun' is an immense encyclopedia of medicine. It contains some of the most illuminating thoughts pertaining to distinction of mediastinitis from pleurisy; contagious nature of phthisis; distribution of diseases by water and soil; careful description of skin troubles; of sexual diseases and perversions; of nervous ailments."

The Canon mentions how new medicines should be tested, below are quotations which have been adapted to modern English:

- The active ingredient must be pure, free from any accidental extraneous quality

- The drug must be used on just one simple disease, not a cluster of diseases

- Test the medication on two contrary types of diseases. Sometimes the essential qualities of a drug may treat one disease effectively, while curing another by accident

- A medication's quality must match the severity of the disease. The heat of one drug may be less than the coldness of a disease, rendering it ineffective

- The whole process must be timed carefully, so that the drug's action is clearly noted, rather than any other confounding factor

- The medication's efficacy must be consistent, with similar results after experimenting with many patients. Otherwise, the trial can't tell whether accidental effects were in play

- Testing must be done on humans, not animals. Testing on a horse or a lion does not prove it will work on humans

Medieval Islam's contribution to human anatomy and physiology

Ibn al-Nafi, an Arab physician born in Damascus in 1213, is thought to be the first person ever to describe the pulmonary circulation of blood. He said he did not like dissecting human corpses because of his own compassion for the human body and the shari'a (code of law based on the Koran). Medical historians believe he probably did his research with animals.The Greek physician, Galen, centuries before had said that blood reached the left ventricle in the heart to the right ventricle through invisible passages in the septum. Al-Nafi believed this was wrong. Al-Nafi wrote:

"The blood from the right chamber of the heart must arrive at the left chamber but there is no direct pathway between them. The thick septum of the heart is not perforated and does not have visible pores as some people thought or invisible pores as Galen thought. The blood from the right chamber must flow through the vena arteriosa (pulmonary artery) to the lungs, spread through its substances, be mingled there with air, pass through the arteria venosa (pulmonary vein) to reach the left chamber of the heart and there form the vital spirit...

"The heart has only two ventricles ...and between these two there is absolutely no opening. Also dissection gives this lie to what they said, as the septum between these two cavities is much thicker than elsewhere. The benefit of this blood (that is in the right cavity) is to go up to the lungs, mix with what is in the lungs of air, then pass through the arteria venosa to the left cavity of the two cavities of the heart and of that mixture is created the animal spirit."

Ancient Greek medicine said that a visual spirit in the eye allowed us to see. Ibn al-Haytham (Al-hazen in Latin) (965-c. 1040), an Iraqi Muslim scientist, explained scientifically that the eye is an optical instrument. He described the anatomy of the eye in great detail and later formed theories on image formation. Al-haytham'sBook of Optics became widely read throughout Europe until the 17th century.

Ahmad ibn Abi al-Ash'ath, an Iraqi doctor, described how a full stomach dilates and then contracts after experimenting on live lions. al-Ash'ath preceded William Beaumont by nearly 900 years in carrying out experiments in gastric physiology.

Abd al-Latif al-Baghdadi (1162-1231), a famous Iraqi physician, historian, Egyptologist and traveler, said that Galen was wrong to say that the lower jaw consists of two parts. On observing the remains of humans who had starved to death in Egypt, he concluded that the lower jaw (mandible) consists of just one bone. In his work, "Book of Instruction and Admonition on the Things Seen end Events Recorded in the Land of Egypt", he wrote:

"What I saw of this part of the corpses convinced me that the bone of the lower jaw is all one, with no joint nor suture. I have repeated the observation a great number of times, in over two thousand heads...I have been assisted by various different people, who have repeated the same examination, both in my absence and under my eyes.."

Sadly, Al-Badhdadi's observation was ignored.

Medieval Islamic drugs and remedies

As in Ancient Greece, Rome and Egypt, Medieval Islamic medications consisted of natural substances, many of which were plant based. Most of the remedies had also been used in ancient Greek and Roman medicines.- Mercuric chloride was introduced by Muslim scholars to disinfect wounds.

- Poppy (Papaver somniferum Linnaeus) - this was used to relieve pain. Poppy seeds contain both codeine and morphine. According to literature, poppy was used to relieve the symptoms of pain from gallbladder stones, fever, toothaches, pleurisy, headaches, and eye pain. It was also used to make people "go to sleep before an operation". Ali al-Tabariwarned was against taking the extract of poppy leaves, saying they could be deadly, and that opium was a poison.

From 800 AD onwards, the use of poppy was restricted to healthcare professionals. - Hemp (Cannabis sativa Linnaeus) - Islamic doctors followed Dioscorides' advice and used the seeds to help during childbirth. Hemp juice was used for earache.

Hemp came into Islamic countries from India around 900 AD. - Fennel - commonly used to calm people down.

- Garlic - had many uses. It was given to people with heart problems.

- Willow - was used as an antiseptic

Did Medieval Islamic doctors perform surgery?

Islamic society built many hospitals, and there was much more surgery going on compared to ancient Greece and Rome. Hospitals were called Bimaristan, which means "house of the sick" in Persian.As there were no proper anesthetics like we have today, it was not possible to carry out sophisticated surgery deep inside the human body. However, doctors used opium to induce sleep before operations.

Many procedures were learnt from Greek and Roman texts.

Surgery was rarely practiced outside hospitals, because of the very high death rate.

Ophthalmologists made advances in surgeries of the eye, and treated patients with cataracts and trachoma.

Cauterization (when the skin or the flesh of a wound is burnt) was a common procedure to prevent infection and stem the bleeding of wounds. Doctors heated a metal rod and placed the red-hot metal on the skin or flesh of a wound; the blood would immediately clot and the wound would have a chance to heal.

Bloodletting was used to restore the balance of humors. Blood would be drained from a vein. Sometimes "wet-cupping" was used to draw blood - a small incision is made on the skin and then a heated cupping glass is placed on it.

Female doctors

Records show that male members of the household did not like having their females being examined by male physicians, unless it was a life-or-death situation. They preferred to have their women and girls examined and treated by females, or by themselves. Even the women were not happy about having a male practitioner present during, for example, childbirth.Of the great civilizations, it was in Medieval Islam that female doctors started to appear in large numbers.

According to the writings of the "medicine of the prophet", men could treat women and women could treat men, even if this meant exposing their genitals when circumstances made it necessary. Various documents during that period mention female physicians, midwives and wet nurses.

What is European Medieval & Renaissance Medicine?

The Medieval Period, commonly known as The Middle Ages spanned 1,000 years, from the 5th to the 15th century (476 AD to 1453 AD). It is the period in European history which started at the end of Classical Antiquity (Ancient History), about the time of the fall of the Western Roman Empire, until the birth of the Renaissance period and the Age of Discovery. The Middle Ages is divided into three periods - the Early, High and Late Middle Ages. The Early Middle Ages are also known as the Dark Ages. Many historians, especially Renaissance scholars, viewed the Middle Ages as a period of stagnation, sandwiched between the magnificent Ancient Roman period and the glorious Renaissance.The Renaissance period (1400s to 1700s). followed the Middle Ages.

Around 500 AD, hoards of Goths, Vikings, Vandals and Saxons, often collectively referred to as "Barbarians", invaded much of Western Europe. The whole area broke up into a large number of tiny fiefdoms - territories run by feudal lords. The feudal lord literally owned his peasants, who were called serfs. These fiefdoms had no public health systems, universities or centers of excellence.

Scientific theories or ideas rarely had the chance to travel, because communication between fiefdoms was poor and perilous. The only places that managed to continue learning and studying science were the monasteries. In many places, monks were the only people who knew how to read and write. Greek and Roman medical records and literature disappeared. Fortunately, Muslim cities in the Middle East had translated most of them and kept them in their centers of learning.

Life was dominated by the Catholic Church

Politics, lifestyles, beliefs and thoughts were dominated by the Roman Catholic Church. People were Christians and believed in the Christian God. Most of them were also superstitious. It was mainly an authoritarian society, you had to believe what you were told, and if you ever questioned it you could be risking your life.Towards the end of the tenth century, around 1066, things began to change. The University of Oxford was born (1167), as was the University of Paris (1110). As the monarchs became owners of more territory, their wealth grew, and their courts became centers of culture. Towns began to form, and with them many public health problems. Trade grew rapidly after 1100.

When the Mongols destroyed Baghdad, fleeing scholars managed to take documents and books with them to the west.

Medical stagnation in the Middle Ages in Europe

Much medical knowledge from the Roman and Greek civilizations was lost, consequently the quality of medical practitioners was poor. The Catholic Church did not allow corpses to be dissected; people were encouraged to pray and fear the consequences of not doing as they were told, or thinking differently from Church teachings. It was not an environment conducive to creativity.Friction developed between the Church and medical practitioners who used incantations as well as Greek, Roman and Islamic methods. Throughout the great civilizations that had preceded the Middle Ages, spells and incantations had persisted, and were used together with herbal and other remedies. The Church insisted that these magical rituals be replaced with Christian prayers and devotions.

Research, development, and observation gave way to an authoritarian system which undermined scientific thinking. There was no money for public health systems. Fiefdoms were at war with each other most of the time.

The authoritarian Church made people believe blindly in what Galen had written. The Church also encouraged people to turn to their saints when seeking treatment and cures for diseases and ailments.

Many people ended up thinking that illness was a punishment from God, and saw no point in trying to find cures. They were taught that repentance for their sins might save them. The practice of penance was born, as well as pilgrimages as a way of finding a cure for illnesses.

Some devout Christian felt that medicine was not a profession a faithful person should go into - if God punished with diseases, might not fighting disease be a move against God? God sent illnesses and cures depending on his will, they believed.

Interpretation of Church teachings varied enormously throughout Western Europe. Some monks, such as the Benedictines, did care for the sick and saw this as a Christian duty, and devoted their lives to that.

Some Christians did come into contact with eminent doctors. During the Crusades, many Christians travelled to the Middle East, and learnt about scientific medicine.

During the 12th century, many medical books and documents were translated from Arabic. Islamic scholars had translated most of the Greek and Roman texts.

Avicenna's The Canon of Medicine, which included details on Greek, Indian and Muslim medicine was translated and became essential reading throughout Western European centers of learning for several centuries. Several other major texts which originated from Hippocrates, Galen, and others were also translated.

Medieval medicine and the theory of Humors

Humorism was a theory put forward by the ancient Egyptians, and then formally reviewed and adopted by Greeks scholars and physicians; it was then taken up by Roman, Medieval Islamic and European doctors, and prevailed right up until the 19th century. The theory, which lasted two thousand years, is now discredited.Believers in humorism said that human health is driven by four different bodily fluids - humors - which influence our health. They have to be in perfect balance. This theory is said to have come from Hippocrates and scholars from his school. A humor was also known as a cambium (plural: cambia/cambiums).

The four humors were (with their links to seasons, organs, temper, and element):

- (Humor) Black bile

Linked to (temper) melancholy, (organ) the spleen, (nature) cold dry, and (element) earth - (Humor) Yellow bile

Linked to (temper) phlegmatic, (organ) the lungs, (nature) cold wet, and (element( water - (Humor) Phlegm

Linked to (temper) sanguine, (organ) the head, (nature) warm wet, and (element) air - (Humor) Blood

Linked to (temper) choleric, (organ) gallbladder, (nature) warm dry, and (element) fire

All diseases and disorders are caused by too much or not enough of one of these humors. An imbalance of humors could be caused by inhaling or absorbing vapors. Medical establishments believed that levels of these humors would fluctuate in the body, depending on what we ate, drank, inhaled, and what we had been doing.

Humor imbalances not would only cause physical problems, but changes in the person's personality as well.

Lung problems were caused by too much phlegm in the body - the body's natural reaction was to cough it up. Restoring the right balance required blood-letting (using leeches), following a special diet, and taking specific remedies.

During Medieval times, most of the world believed in the four humors theory. Monasteries, which led medical research and practice in Medieval Europe had extensive herb gardens for the production of remedies - certain herbs were ascribed to a humor.

The monks believed in the Christian Doctrine of Signature which said that God would provide some kind of relief for every disease, and that each substance had a signature which indicated how effective it might be. For example, some seeds that looked like miniature skulls, such as the skullcap, were used to treat headache.

The most famous medieval book on herbs is probably the Read Book of Hergest (1400) which was written in Welsh around 1390.

European Medieval hospitals

Hospitals had a slightly different meaning during the Middle Ages, compared to what we understand today. They were more like hospices, or homes for the aged and needy. Not only the sick found their place in hospitals, but also paupers, blind people, pilgrims, travelers, orphans, people with mental illness, and other destitute individuals. For those in desperate need, the Christian thing to do was provide hospitality, i.e. food and shelter, and medical care if necessary.During the Early Middle Ages, hospitals were not used much for the treatment of sick people, unless they had particular spiritual needs or nowhere to live.

Monasteries throughout Europe had several hospitals, which provided medical care and spiritual guidance.

The Hotel-Dieu, founded in Lyons in 542 AD by Childebert I, king of the Franks, is the oldest hospital in France. The 28th Bishop of Paris founded the Hotel-Dieu of Paris in 652 AD. Santa Maria Della Scala, Siena, built in 898 AD is the oldest hospital in Italy.

The oldest hospital in England was built in 937 AD by the Saxons. After the Norman Conquest (Battle of Hasting, 1066), many more were built. A well known hospital in London today, St. Bartholomew's of London, was build in 1123. A hospital was called a hospitium or hospice for pilgrims. As time went by, the hospitium developed and became more like what we today understand as a hospital, with monks providing the expert medical care and lay people helping them.

During the Crusade in the 12th century, the building of hospitals became more of a priority. An enormous number of hospitals were founded during the 13th century, especially in Italy; over a dozen were built in Milan alone. By the end of the 14th century Florence had over 30 hospitals, some of them were architectural works of art.

The plagues of the 14th century triggered the construction of even more hospitals.

According to Benjamin Lee Gordon, who wrote the book "Medieval and Renaissance Medicine" in 1959, the hospital as we know it today was invented by the French, but was originally set up to help plague victims, to separate lepers from the community, and later on to provide shelter for pilgrims.

What was Medieval surgery like?

There were some advances in surgery during the Middle Ages. Barbers-come-surgeons learnt useful skills tending to wounded soldiers in the battlefield. Monks and scientists also discovered some valuable plants with powerful anesthetic and antiseptic qualities.This long period of stagnation in medicine had one exception, historians say - "surgery".

Barbers were in charge of surgery in medieval Europe, not doctors. During the Middle Ages there were frequent battles and wars, some of them lasting up to 100 years. The skills of surgeons were much sought after in the battlefield. Theodoric of Lucca, son of Hugh of Lucca who was appointed surgeon for Bologna in Italy during the 13th century, said of the clever way of dealing with wounds:

"Every day we see new instruments and new methods (to remove arrows) being invented by clever and ingenious surgeons."

Hugh of Lucca noticed that wine was an effective antiseptic; it was useful for washing out wounds and preventing further infection. This observation would have been an empirical one because at that time people had no idea that infections were caused by germs. His observation was heeded by many surgeons who started using wine for treating wounds, but many continued using ointments and/or cauterization. Hugh believed pus was not a healthy sign, something most other surgeons disagreed with. Many saw pus as a good sign of the body ridding itself of toxins in the blood.

The following natural substances were used by medieval surgeons as anesthetics:

- Mandrake roots

- Opium

- Gall of boar

- Hemlock

Poor hygiene and infection link - unfortunately, nobody knew that lack of hygiene dramatically increases the risk of infection, especially during and after surgery. Many wounds were fatal because of infection caused by poor hygiene.

Trepanning - some patients with neurological disorders, such as epilepsy, would have a hole drilled into their skulls "to let the demons out".

During the Renaissance surgery advanced much faster

From the 1450s onwards, as the Middle Ages gave way to the Renaissance, advances in medical practice accelerated dramatically:- Girolamo Fracastoro (1478-1553), an Italian doctor, poet, and scholar in geography, astronomy and mathematics, put forward the idea that epidemics may be caused by pathogens from outside the body that may be passed on from human-to-human by direct or indirect contact.

Fracastoro wrote:""I call fomites (Latin for "tinder") such things as clothes, linen, etc., which although not themselves corrupt, can nevertheless foster the essential seeds of the contagion and thus cause infection."

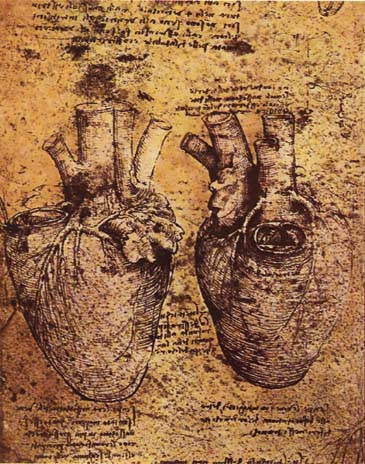

He also suggested using mercury and "guaiaco" as a cure for syphilis. Guiaiaco is the oil from the Palo Santo tree, a fragrance used in soaps. - Andreas Vesalius (1514 -1564), a Flemish anatomist, physician, was the author of one of the most influential books on human anatomy "De Humani Corporis Fabrica (On the Structure of the Human Body)". He dissected a corpse and made a careful examination, detailing the structure of the human body. Technical and printing development during the Renaissance made it possible for this book to be made, with incredibly detailed illustrations (compared to anything that had been produced before).

- William Harvey (1578 - 1657), an English doctor was the first person to properly describe the systemic circulation and properties of blood, which is pumped around the body by the heart. In 1242 Avicenna had described a rudimentary account, but he had not fully understood the pumping action of the heart and how it was responsible for sending blood to every part of the body.